Join-in Group Silk Road China Tours

About Us | Contact us | Tourist Map | Hotels | Feedback

The Silk Road History

Overview:The Silk Road, cross Asia from China to Europe, is not really a single road, rather a sea & land network of related ancient trade routes through Xian, Dunhuang, Lanzhou, Turpan, Kashgar and Central Asian countries.

The Silk Road was not actually a single paved road. It is a historical sea & land network of interlinking ancient trade routes across the Afro-Eurasian landmass that connected East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean and European world, even parts of North and East Africa. The Silk Road was a name to all routes through Syria, Turkey, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, India to China.

As a 4000-mile (6,437 kilometres) trip, the Silk Road was given its name by German geographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen in 1970s, from the lucrative Chinese silk trade which was carried out along its length. Some scholars prefer the term "Silk Routes" for reason that the road connected an extensive transcontinental network of trade routes, though few were more than rough caravan tracks. One poem calls it "The Golden Road to Samarkand".

Trade on the Silk Road was a significant factor in the development of the civilizations of China, the Indian subcontinent, Persia, Europe and Arabia. Though silk was certainly the major trade item from China, many other goods were traded, and various technologies, religions and philosophies, as well as the bubonic plague (the "Black Death"), also traveled along the Silk Routes.

Early History of the Silk Road

The Silk Road crosses Asia from China to Rome began during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD). At one end, Rome had gold and silver and precious gems; another end China had silk and spices and ivory; Each had something the other wanted. Ideas also traveled along the Silk Road trade that affected everyone.

In the west, the Greek empire was taken over by the Roman empire. Even at that time before the journey of Zhang Qian, some earlier individual traders and caravans trade routes across the continents already existed for small quantities of Chinese goods, including silk, to reach the west. The main traders during Antiquity were the Indian and Bactrian traders, then from the 5th to the 8th century the Sogdian traders, then afterward the Arab and Persian traders. These traders and caravans may have started to make the journey in search of new markets despite the danger or the political situation of the time.

The Development of the Route

The central Asian sections of the trade routes were expanded around 114 BC by the Han dynasty, largely through the missions and explorations of Zhang Qian. The development of Central Asian trade routes caused some problems for the Han rulers in China. Xiongnu and Tibetan bandits soon learned of the precious goods travelling up the Gansu Corridor and skirting the Taklimakan, and took advantage of the terrain to plunder these caravans. Thus sections of 'Great Wall' were built along the northern side of the Gansu Corridor, to try to prevent the bandits from harming the trade; Sections of Han dynasty wall can still be seen as far as Yumen Guan, well beyond the recognised beginning of the Great Wall at Jiayuguan. However, these fortifications were not all as effective as intended, as the Chinese lost control of sections of the route at regular intervals.

After the Western Han dynasty, successive dynasties brought more states under Chinese control. Settlements came and went, as they changed hands or lost importance due to a change in the routes. The chinese garrison town of Loulan, for example, on the edge of the Lop Nor lake, was important in the third century A.D., but was abandoned when the Chinese lost control of the route for a period. Many settlements were buried during times of abandonment by the sands of the Taklimakan, and could not be repopulated.

The most significant commodity carried along this route was not silk, but religion. Buddhism came to China from India this way, along the northern branch of the route.

The Greatest Years

The height of the importance of the Silk Road was during the Tang dynasty, with relative internal stability in China after the divisions of the earlier dynasties since the Han. The individual states has mostly been assimilated, and the threats from marauding peoples was rather less.

The art and civilisation of the Silk Road achieved its highest point in the Tang Dynasty. Changan, as the starting point of the route, as well as the capital of the dynasty, developed into one of the largest and most cosmopolitan cities of the time. By 742 A.D., the population had reached almost two million, and the city itself covered almost the same area as present-day Xian, considerably more than within the present walls of the city. The 754 A.D. census showed that five thousand foreigners lived in the city; Turks, Iranians, Indians and others from along the Road, as well as Japanese, Koreans and Malays from the east. Rare plants, medicines, spices and other goods from the west were to be found in the bazaars of the city.

During this period, in the seventh century, the Chinese traveller Xuan Zhuang crossed the region on his way to obtain Buddhist scriptures from India. He followed the northern branch round the Taklimakan on his outward journey, and the southern route on his return; he carefully recorded the cultures and styles of Buddhism along the way. On his return to the Tang capital at Changan, he was permitted to build the `Great Goose Pagoda' in the southern half of the city, to house the more than 600 scriptures that he had brought back from India. He is still seen by the Chinese as an important influence in the development of Buddhism in China, and his travels were dramatised by in the popular classic "Tales of a Journey to the West".

The Mongols Period

But the final shake-up that occurred was to come from a different direction; the hoards from the grasslands of Mongolia. Under the leadership of Genghis Khan, they rapidly proceeded to conquer a huge region of Asia. Great Khan, a title which was inherited from by Kublai Khan. Kubilai completed the conquest of China, subduing the Song in the South of the country, and established the Yuan dynasty. The partial unification of so many states under the Mongol Empire allowed a significant interaction between cultures of different regions. The route of the Silk Road became important as a path for communication between different parts of the Empire, and trading was continued.

It was at the duration that Europeans first ventured towards the lands of the 'Seres'. The earliest were probably Fransiscan friars who are reported to have visited the Mongolian city of Karakorum. The first Europeans to arrive at Kubilai's court were Northern European traders, who arrived in 1261. However, the most well known and best documented visitor was the Italian Marco Polo.

The book, The Marco Polo Travels describes the way of life in the cities and small kingdoms through which he passed, with particular interest on the trade and marriage customs. Though many details may be debate, the book captured public notice at the time, and added much to what was known of Asian geography, customs and natural history as a whole.

The Decline of the Route

However, the Mongolian Empire was to be fairly short-lived. Despite the presence of the Mongols, trade along the Silk Road never reached the heights that it did in the Tang dynasty. The steady advance of Islam, temporarily halted by the Mongols, continued until it formed a major force across Central Asia. The overland problems of 'tribal politics' between the different peoples along the route, and the presence of middlemen, all taking their cut on the goods, prompted this move.

The demise of the Silk Road also owes much to the development of the silk route by sea. It was becoming rather easier and safer to transport goods by water rather than overland. Ships had become stronger and more reliable, and the route passed promising new markets in Southern Asia.

The sea route, however, suffered from the additional problems of bad weather and pirates. In the early fifteenth century, the Chinese seafarer Zhang He commanded seven major maritime expeditions to Southeast Asia and India, and as far as Arabia and the east coast of Africa. Diplomatic relations were built up with several countries along the route, and this increase the volume of trade Chinese merchants brought to the area. In the end, the choice of route depended very much upon the political climate of the time.

The attitude of the later Chinese dynasties was the final blow to the trade route. The isolationist policies of the late Ming dynasties did nothing to encourage trade between China and the rapidly developing West. This attitude was maintained throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, and only started to change after the Western powers began making inroads into China in the nineteenth century. That was the one-century fall of China!

Foreign Influence

Renewed interest in the Silk Road only emerged among western scholars towards the end of the nineteenth century. This emerged after various countries started to explore the region for their territories expanding under interest involvement of the foreign powers. The British, in particular, were interested in consolidating some of the land north of their Indian territories. They saw the presence of Russia as a threat to the trade developing between Kashgar and India, and the power struggle between these two empires in this region came to be referred to as the "Great Game".

The study of the Road really took off after the expeditions of the Swede Sven Hedin in 1895. He was an accomplished cartographer and linguist, and became one of the most renowned explorers crossed the Pamirs to Kashgar, then Turpan of the time. After Hedin, the archaeological race started. Many precious manuscripts frescoes from the grottos were found at some ancient ruins on the Silk Road.

The treasures of the ancient Silk Road are now scattered around museums in perhaps as many as a dozen countries. The biggest collections are in the British Museum and in Delhi, due to Stein and in Berlin, due to von Le Coq. The manuscripts attracted a lot of scholarly interest, and deciphering them is still not quite complete.

The Present Day

The Silk Road, after a long period of hibernation, has been increasing in importance again recently for the reason that the powerful fight of man against the desert to solvel many biggest problems for the early travellers. The trade route itself is also being reopened. The sluggish trade between the peoples of Xinjiang and the rest of China has developed quickly; Many of these nationalities are now participating in cross-border trade, regularly making the journey to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

In China, the railway connecting Lanzhou to Urumchi has been extended to the border with Kazakhstan, where on 12th September 1990 it was finally joined to the former Soviet railway system, providing an important route to the new republics and beyond. This Eurasian Continental Bridge, built to rival the Trans-Siberian Railway from China the route passes through Kazakhstan, Russia, Byelorussia and Poland, before reaching Germany and the Netherlands.

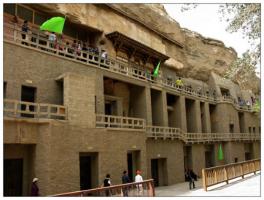

Since the intervention of the West last century, interest has been growing in this ancient trade route. The books written by Stein, Hedin and others have brought the perceived oriental mystery of the route into western common knowledge. Instilled with such romantic ideals as following in the footsteps of Marco Polo, a rapidly increasing number of people have been interested in visiting these desolate places since China opened its doors to foreign tourists at the end of the 1970s. The benefit of tourist potential has encouraged the authorities to do their best to research and protect the remaining sites. The Mogao grottos were probably the first place to attract this attention;

Archaeological excavations have been started by the Chinese where the foreigners laid off; significant finds have been produced from such sites as the Astana tombs, where the dead from the city of Gaochang were buried. Finds of murals and clothing amongst the grave goods have increased knowledge of life along the old Silk Road; the dryness of the climate has helped preserve the bodies of the dead, as well as their garments.

There is still a lot to see around the Taklimakan, mostly in the form of damaged grottos and ruined cities. Whilst some people are drawn by the archaeology, others are attracted by the minority peoples; there are thirteen different races of people in the region, apart from the Han Chinese, from the Tibetans and Mongolians in the east of the region, to the Tajik, Kazakhs and Uzbeks in the west. Others are drawn to the mysterious cities such as Kashgar, where the Sunday market maintains much of the old Silk Road spirit, with people of many different nationalities selling everything from spice and wool to livestock and silver knives. Many of the present-day travellers are Japanese, visiting the places where their Buddhist religion passed on its way to Japan.

Although Xinjiang is opening up, it is still not an easy place to travel around. Apart from the harsh climate and geography, many of the places are not fully open yet, and, perhaps understandably, the authorities are not keen on allowing foreigners to wander wherever they like, as Hedin and his successors had done. The desolation of the place makes it ideal for such aspects of modern life as rocket launching and nuclear bomb testing. Nevertheless, many sites can be reached without too much trouble, and there is still much to see.

From its birth before Christ, through the heights of the Tang dynasty, until its slow demise six to seven hundred years ago, the Silk Road has had a unique role in foreign trade and political relations, stretching far beyond the bounds of Asia itself. It has left its mark on the development of civilisations on both sides of the continent. However, the route has merely fallen into disuse; its story is far from over. With the latest developments, and the changes in political and economic systems, the edges of the Taklimakan may yet see international trade once again, on a scale considerably greater than that of old, the iron horse replacing the camels and horses of the past.